Why Am I Writing This Blog?

- Toby

- May 10, 2022

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 7, 2022

I love stories – movies, plays, tv shows, novels, audio dramas, fortune cookie slips… the medium doesn’t matter as long as it’s a good story.

So why is it so hard to tell a good story?

The limits of three-act structure

When I was in 7th grade, I learned about three-act structure. You see, in every story there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. Or, as my teacher put it:

Act I: Get your main character into a tree.

Act II: Throw rocks at your character.

Act III: Get your main character down from the tree.

Simple, no?

Turns out, no. I sat down to write and put a character up in a tree. I threw both metaphorical and literary rocks at the character. They cried (the metaphorical rocks kept hitting them). And then…

I had no idea what to do. There were an infinite number of ways the story could go and none of those ways seemed like an obvious method for the character to get down other than falling out of the tree into a lava lake and drowning.

So I started another story. Same problem. Eventually, I decided that I just ‘wasn’t good at structure’. It took another decade before I started to realize the problem wasn’t simply my own incompetence.

I think that the way we teach stories is wrong.

Using the formula I learned in 7th grade, almost no one is any good at structure. Because that isn’t a structure, it's a sequence.

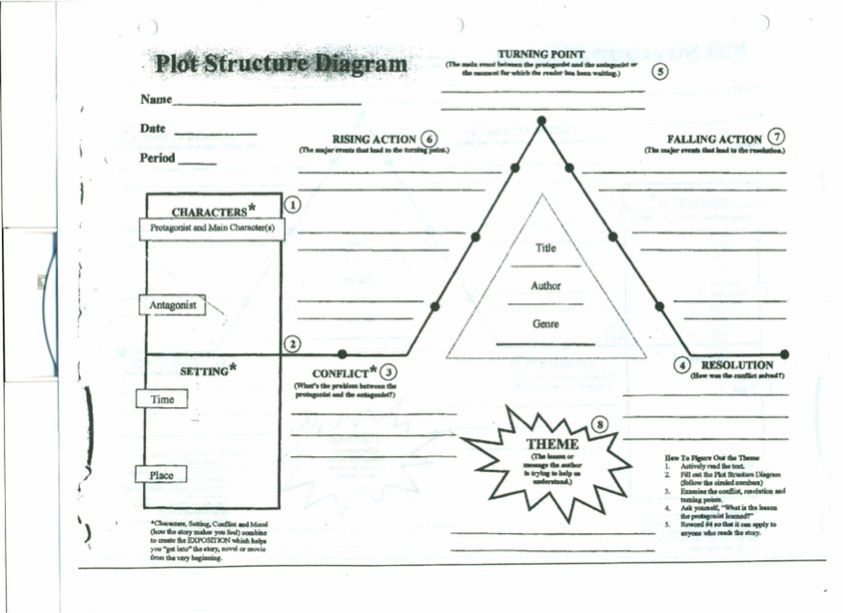

This is the sort of thing we teach in elementary school.

It includes not-so-helpful facts like ‘a story must have a setting’. That’s true. But it’s sort of like a worksheet about icebergs that starts by telling us that they’re “generally white because they are covered in snow, but can be green, blue, yellow, black, striped, or even rainbow-colored.” (So says Wikipedia.)

Not wrong, but it’s just sort of missing the point.

Once we hit middle and and high school, we start to see lots of maps like these:

The people who created these maps were describing exactly what they are experiencing when they hear, watch, or read stories – after all, in pretty much every story there’s a conflict. The conflict builds. And eventually, it reaches a peak and resolves in some way.

I just don’t see the triangles helping me figure out how to get the little guy out of the tree.

If you keep trying to write stories into adulthood, soon this is the sort of thing that pops up when you google storytelling basics. The article has “10 important basic points of storytelling.” For example:

Point #1: “Include a beginning, middle and end.”

Back to that again. And it’s not like the guy isn’t smart – he has many other posts that are spot on. It’s just that he’s working from that same starting place as my 7th grade teacher.

Do some digging and you’ll soon reach something like this. Which legitimately has some great info in it. It’s just that it also has helpful facts like –

You must always start with a hook. Follow that up with the pinch point. Then the midpoint is the turning point that forces the hero to switch from passive to active. Right before the climax is the lowest point for the protagonist where it seems that all hope is lost. Finally, the climax (when the “highest emotions happen”) follows and then the resolution.

Ah, yes. Confused how to implement this?

Well that just proves that you aren’t very good at structure either.

I want to help people tell better stories.

If we hope to create unified stories that are compelling and effective, we first need a clear and basic understanding of story mechanics that goes beyond a plot structure diagram that shows a triangle with one side labeled ‘rising action’ and the other labeled ‘falling action’, or an intricate 37-point plan detailing an order of consecutive pinch points.

I’ve been studying how stories work for the past decade. I still have a lot to learn, but here’s what I’ve got so far.

Comments